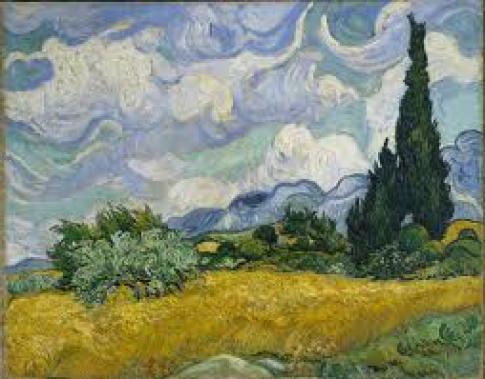

‘Van Gogh at Work’, Amsterdam

Van Gogh’s working practice is more fully chronicled than any other major artist, owing to the survival of hundreds of his letters, most of them addressed to his art-dealer brother Theo. Full to overflowing with self-examination, they faithfully trace each step in Vincent’s 10-year struggle to find his own way.

By Robin Blake

Just reopened, Amsterdam’s Van Gogh Museum shines new light on the artist’s work – and on the fickle chemistry of his palette

As if to prove that there is no artist more passionately loved than Vincent Van Gogh, Amsterdammers turned out in their thousands on May Day, impatient to see the Van Gogh Museum as it opened its doors after a seven-month refit. They were queueing to see the reopening exhibition Van Gogh at Work, which offers the chance to see important loans – among them “Sunflowers” from London, hung alongside the museum’s own version, and “The Penitentiary” from Moscow.

There are also visiting works by fellow artists from whom Van Gogh drew strength – Gauguin, Emile Bernard, Degas, Toulouse-Lautrec, Signac, Monticelli – and artefacts such as the artist’s only surviving palette, still loaded with paint, which has come for the occasion from Paris. But these loans are in support of what is essentially a rehang of the permanent collection, whose aim, expressly didactic, is to provide the results of a lengthy programme of research.

Van Gogh’s working practice is more fully chronicled than any other major artist, owing to the survival of hundreds of his letters, most of them addressed to his art-dealer brother Theo. Full to overflowing with self-examination, they faithfully trace each step in Vincent’s 10-year struggle to find his own way. They mention in passing around 600 of his works, and discuss many even before the paint was dry. What can science add, the museum has been asking, to what is already a plethora of knowledge?

The main research tools applied are X-rays, infrared reflectography, the microscope and the chemical analysis of paint. And while a good deal of the information obtained is mainly of interest to conservators, much of it confirms or adds to what we know from the artist’s letters.

We learn where he bought his canvases, and the precise type of tea towel he would paint on when funds did not run to artist’s canvas. We find him covering over old paintings, sometimes repeatedly, or turning them around and making new paintings on the back. We learn – from the discovery of grains of sand or pollen blown on to the wet paint – which paintings were done outdoors.

Few gallery-goers think for long about the colour of the ground upon which paintings are made but here the matter is researched in illuminating detail. At one crucial moment in his development, Van Gogh switched for a period from the use of a pale ground to a darker brown-pink one, which closely resembled the colour of his wooden palette. This enabled him to see the exact effect of different paint blends before he applied them, thereby avoiding false starts and helping him acquire the speed that became a vital characteristic of his mature brushwork.

There is also important, if dismaying, information about the way Van Gogh’s colours have changed over time. Colour became his consuming interest from 1885, after which he saw painting as a dramatic conversation – sometimes a conflict – between colours. Regarding “The Night Café” (which is not in the exhibition), he wrote to Theo: “I have tried, by contrasting soft pink with blood-red and wine-red, soft Louis XIV-green and Veronese green with yellow-greens and harsh blue-greens, all this in an atmosphere of an infernal furnace in pale sulphur, to express the powers of darkness in a common café.” This insistence that colour is in itself expressive, an intentional departure from impressionist theory, is one of the marks of Van Gogh’s modernism; his use of modern pigments was another, though, in this case, there were repercussions.

Many previously unknown industrial dye-colours, inorganic and artificial, were being invented at this time, enabling artists’ colourmen to launch new pigments of startling brightness and intensity. Such paints, naturally spurned by traditionalists, were bound to interest the avant-garde, and Van Gogh took them up with enthusiasm. Yet not all of them stayed over time at the same spot on the spectrum where they started.

One of the most striking examples is Geranium Lake, an oil paint whose exceptionally bright red was obtained from the dye eosin, which had been discovered in Germany in 1873, and which Van Gogh began to use from the beginning of 1888, after moving from Paris to Arles. He employed it, for instance, in the series of fruit trees in blossom during his first April in the south, and continued to do so for the remaining three years of his life. But Geranium Lake is fatally susceptible to the effect of light, relentlessly fading until it disappears completely. As a result, the blossoming fruit trees – and indeed all paintings in which Van Gogh used that colour, either raw or blended to create pinks and purples – now have a very different appearance from the one originally intended.

The case is proved in the Van Gogh at Work show by the microscopic examination of one paint fragment in cross-section, where the core of the sample shows up as rosy while the top few micrometers, the paint surface, is simply white.

Some of the affected paintings are among Van Gogh’s most famous. Posting a sketch of “The Bedroom” to Theo in October 1888, Vincent stressed that in the painting, “everything depends on colour ... the walls are pale violet. The floor is red tiles. The wood of the bed is the yellow of fresh butter, the sheet and the pillows very light lime green. The blanket scarlet. The window green. The washstand orange, the basin blue.” Nowadays those walls are no longer pale violet but duck-egg blue, a change that affects the whole appearance of the canvas.

Such alterations are bound to destabilise our perception of these paintings, especially when they exist in more than one version. Then the question arises of whether any variations are the artist’s intention, or a result of exposure to different degrees of light. “The Bedroom” is a case in point, and in September there will be a useful opportunity to compare the Amsterdam version with the one in the Art Institute of Chicago, when the latter arrives on extended loan.

The purely technical and material consideration of Van Gogh is no barrier to a direct enjoyment of his work: this is not like getting hung up about Beethoven’s piano-strings or Nijinsky’s dance pumps. The material choices Van Gogh made were often determined by his dire poverty, and his dependence on Theo’s financial support. That is why they matter, and why this exhibition is much more than a show for Van Gogh completists. It is for anyone at all who cares for him, in and beyond Amsterdam.

Copyright The Financial Times Limited 2013.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us Digg

Digg

Post your comment