The legacy of the Russian revolution, 100 years on

The 1917 revolution and its legacy may resist straightforward analysis, but one thing is clear — coups and revolutions still shape people's political horizons.

Larisa Sotieva

The 1917 revolution and its legacy may resist straightforward analysis, but one thing is clear — coups and revolutions still shape people's political horizons.

The human quest for knowledge relies heavily on the connection between the present and memories of the past.

From a conflict perspective, one should be particularly mindful of this. Drawing on conclusions about the present, we forecast and build the future, relying on things of which we are “certain” — things in the past. Yet the past is slippery and unreliable: it can be retold and reinterpreted, depending on our worldview and location. Through the construction of collective memory, the future, in turn, often becomes an effective mechanism for manipulation at both the individual and the societal level.

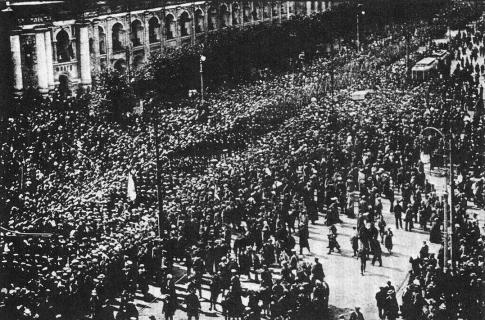

November 2017 will mark one hundred years since the Russian revolution, the revolution that set out to destroy the entire pre-Soviet world and create a new one from its ruins. Transforming the development dynamics of this entire space, the Soviet period changed people’s lives beyond recognition. The Revolution made a profound impact on the thinking and behaviour of later generations, and on the outside world’s view of these societies. The legacy of revolution will long continue to provoke contradictory experiences and interpretations both within and outside this context, and to contribute to conflict at many different levels.

A century ago, revolutionaries were busy conquering the hearts and minds of the masses with their simple, yet effective, slogans. The lines from “The Internationale” “The earth shall rise on new foundations/ We have been naught, we shall be all” would likely appeal to millions of us frustrated individuals all over the world, even today.

Declaring their protest to be a fight for justice, equality and freedom for workers and peasants, the revolutionaries nonetheless proceeded to kill millions of them, while also exterminating and banishing the nobility and intelligentsia.

The Communists’ advent to power through radical protest, blood and violence created the collective belief that revolution is a simple, accessible and effective tool to change an existing order

In the 1970s, the ideological element of my Soviet childhood included emotional films about the roots of the revolution and the reasons behind the propensity for protest. I recall a scene from Battleship Potemkin, set during the revolution of 1905, when mutiny erupted on the ship after sailors were given rancid meat. I must have been shocked by what ensued, as I have been extra cautious about the freshness of my meat ever since!

Thanks to seventy years of propaganda that portrayed the Revolution as the only fair and inevitable course of action, Soviet collective memory registered the event as the main tool for achieving change. This mechanism came into play once more, charged with conflict, during the fall of the USSR, when geographical borders, the borders of identity and other boundaries were redrawn. It is through inertia that the processes of revolution and of the USSR’s dramatic collapse are still ongoing in the post-Soviet space today, manifesting in coups, colour revolutions and conflicts, the consequences of which we at International Alert are working on.

The Communists’ advent to power through radical protest, blood and violence created the collective belief that revolution is a simple, accessible and effective tool to change an existing order — and one which must be guarded against by those in power. They proceeded to strictly censor information, social movements and freedom of expression, effectively closing the country.

However, this closure was not altogether negative — it also played a positive role in stimulating desire for knowledge and forming an intellectual elite. During Soviet times, people risked their lives to discover the world around them and to broaden their horizons. While information is more freely available today, the opposite trend has emerged, as people choose to isolate themselves.

As a child, I would sometimes be woken up by radio static. My father would listen to the radio at night and would discuss the programmes over breakfast with my mother. Aware of some secret, I was immensely curious. Once, I overheard the name “Sakharov” and found it funny (in Russian, it means Mr Sugar). My father warned me not to mention it at school. Years later, I found out that he had been tuning in to Radio Liberty at midnight, and that the static was a result of the KGB attempting to jam the signal.

The Communists certainly succeeded in creating a remarkable world. Closed to the outside world, the Soviet Union was in some respects open and humane on the inside, offering sufficient space for self-development. For generations, Soviets from families of workers and peasants achieved international success in science and the arts. Gender equality in the USSR could be compared to that of Scandinavian countries today. Women were encouraged to take up places in education and indeed all forms of employment. The state had a monopoly over a complex bureaucratic and ideological system.

However, many people found ways to develop their potential in accordance with their values. This was sometimes achieved by fighting the system, but most often by avoiding it altogether.

Critical views still bring punishment, and corruption remains an effective social institution. Post-Soviet societies also still often see revolution as a legitimate tool for social change

Dissidence was something of an institution. The state fought against it through a special punitive system, which branded dissidents as criminals, traitors and enemies of the people. Another institution was the “thieves-in-law” (vory v zakone), a criminal network with its own strict code of conduct. Both institutions survive in many post-Soviet states to this day — for example, news of the deaths of crime lords can often be found alongside obituaries of politicians or famous scientists in Russian media. Dissidents continue to receive harsh treatment in many post-Soviet countries.

In the USSR, social status was determined in a very different way to the west. Relationships between people were not based on money. In Soviet society, the drive for greater wealth arguably declined. People felt they had the same amount of money they had always had, and were confident that they would have exactly the same amount in the future.

Status and prestige were mainly dependent on education and high moral standards. Individuals could achieve much through talent and hard work. The nobility and the merchant class might have been eradicated, but a new social mechanism had formed in their place through which people could gain elite social status and which was not based on communist ideology. Higher education was not only a path to knowledge, but also status — education was pretty much the only means of gaining status for most. This led to corruption, which affected higher educational establishments in particular.

Occasionally, I have the pleasure of meeting and indulging in long chats with some of my good old friends from the intelligentsia. When we part, I cannot help feeling that we are similar to dinosaurs — when we become extinct, there will be no one left with our experience or world view. No one will be able to talk about the roots of our internal and external conflicts, or explain how to explore them effectively, using all the positive resources from the Soviet legacy, resources which still exist in cultural and social interactions.

Examining all these processes from the point of view of working with conflict, I cannot help but think about the legacy of the USSR, as well as its collapse in the 1990s, and the behaviours it spawned. Through inertia, many of these are still present today — critical views still bring punishment, and corruption remains an effective social institution. Post-Soviet societies also still often see revolution as a legitimate tool for social change. Given all this, I have come to the conclusion that, in attempting to forecast post-Soviet social processes, a combination of historical, cultural, philosophical, scientific and political approaches are necessary. This combination is the most appropriate for analysing the connections between the past, present and future.

Sometimes, while it is clearly essential to focus on the present and the future, it is also important to draw on the past and acknowledge the effects of collective memory and its related systems in determining those behaviours and incentives within society which either foster or obstruct progress towards peace. In this way, our “yesterday” can be harnessed in a way to benefit both “today” and “tomorrow”./OD

del.icio.us

del.icio.us Digg

Digg

Post your comment