Mark Twain, Tech Prophet

The phone call is fanciful—the first transcontinental phone call didn’t occur until 1915...

David A. Graham

A short story published in The Atlantic in 1878 may contain the first literary reference to a telephone—along with striking insights into modern dating.

Mark Twain’s reputation for spotting trends in technology is not great. His most famous foray ended poorly, after the great man of letters fancied himself a man of letterpress as well, and invested heavily in the Paige Compositor, a typesetting machine that bankrupted him.

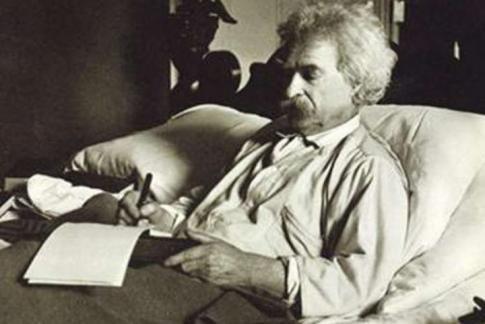

But what if Twain was, in fact, a prescient scout for new innovations? The Times Literary Supplement’s always amusing NB column—which also unearthed this image of Proust playing air guitar on a tennis racket—has been searching for literary firsts, such as the earliest mention of a telephone. TLS readers came up with Gilbert and Sullivan’s HMS Pinafore, which premiered in May 1878. But Mark Lasswell of The Weekly Standard came up with an even earlier reference: Twain’s “The Loves of Alonzo Fitz Clarence and Rosannah Ethelton,” a short story that The Atlantic published in its March 1878 issue. As Lasswell notes, that makes it just 24 months after Alexander Graham Bell was awarded the first patent for a telephone.

The story is weird enough to deserve more than a mere footnote for early phone adoption. Alonzo, the first titular character, is what readers today would identify as an exemplar of stereotypical Millennial dissolution: He is lazy, slovenly, entitled, romantically uninvolved, and living with his mother in Maine. He is dissuaded from leaving the house by poor weather. “No going out to-day. Well, I am content. But what to do for company? Mother is well enough, Aunt Susan is well enough; but these, like the poor, I have with me always,” he tells himself, no doubt thinking it droll. Eventually, he turns to technology. Naturally, it fails him. His clock is wrong. When he pushes buttons to summon a servant and then his mother, they, likely exasperated by his indolence, don’t answer, though Alonzo blames it on dead batteries.

Finally, like a good Millennial, he reaches for an all-purpose entertainment device: his telephone. Alonzo calls Aunt Susan, though Twain doesn’t make his method explicit, apparently expecting the patrician Atlantic readership to figure it out.

He sat down at a rose-wood desk, leaned his chin on the left-hand edge of it, and spoke, as if to the floor: “Aunt Susan!”

A low, pleasant voice answered, “Is that you, Alonzo?”

Susan, it transpires, is in San Francisco. She has greater patience than Alonzo’s mother, but slyly passes the line over to Rosannah, who seems to be a young woman boarding with her, saying, “You are both good people, and I like you; so I am going to trust you together while I attend to a few household affairs. Sit down, Rosannah; sit down, Alonzo. Good-by; I shan’t be gone long.”

The phone call is fanciful—the first transcontinental phone call didn’t occur until 1915—but in speaking with Susan, Alonzo alludes to the fact that they appear to be speaking on a party line, which threatened the privacy of users. “Don’t be afraid,—talk right along; there’s nobody here but me,” Aunt Susan tells him. This is especially important to flirtatious young chatters like Alonzo and Rosannah. The two speak for two hours on the phone, recreating the experience of many an infatuated teenager; soon, they have fallen in love, and she has broken off a relationship with another young man, who vows his revenge and visits Alonzo to extract it.

Disguised, the spurned suitor explains a new device that rings as an early expression of concern about privacy and cybersecurity.

“At present,” he continued, “a man may go and tap a telegraph wire which is conveying a song or a concert from one State to another, and he can attach his private telephone and steal a hearing of that music as it passes along. My invention will stop all that.”

“Well,” answered Alonzo, “if the owner of the music could not miss what was stolen, why should he care?”

“He shouldn’t care,” said the Reverend.

“Well?” said Alonzo, inquiringly.

“Suppose,” replied the Reverend, “suppose that, instead of music that was passing along and being stolen, the burden of the wire was loving endearments of the most private and sacred nature?”

Alonzo shuddered from head to heel. “Sir, it is a priceless invention,” said he; “I must have it at any cost.”

The faux inventor manages to wreck Alonzo and Rosannah’s relationship while demonstrating the dangers of insufficiently private telecommunications. Alonzo, heartbroken, sets out to find her, using what Lasswell identifies as the first portable phone in all of literature, too. Using the hacking trick identified by his rival, Alonzo travels the country, listening in to phone calls and hoping to hear Rosannah’s distinctive off-key singing.

“Strangers were astounded to see a wasted, pale, and woe-worn man laboriously climb a telegraph pole in wintry and lonely places, perch sadly there an hour, with his ear at a little box, then come sighing down, and wander wearily away,” Twain writes. “Sometimes they shot at him, as peasants do at aeronauts, thinking him mad and dangerous. Thus his clothes were much shredded by bullets and his person grievously lacerated. But he bore it all patiently.”

Finally (some spoilers ahead) the couple are united and married—by telephone, as Alonzo remains on the East Coast, in recovery from his travails, while Rosannah is in Hawaii. Only after the long-distance nuptials do the couple meet in the flesh, as it were, for the first time.

This remote matrimony seems more shocking than Twain’s early adoption of the telephone as a literary device, or even of his suggestion of a “portable telephone” or concern for privacy and the dangers of hacked telecommunications. In portraying a relationship begun and brought to marriage entirely via long-distance telecommunication, Twain seems to prefigure a very modern sort of romance, foreshadowing even online dating.

The science-fiction strain in Twain’s writing is underappreciated, even though his 1889 time-travel novel A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court is well-known. Maybe Twain’s mistake was having his Yankee engineer travel back in time, whereas H.G. Wells’s time traveler, though he would not set off until six years later, leapt forward. In “Sold to Satan,” the Tempter is made of radium, the newly discovered radioactive element. Twain has more recently been crowned as a prophet of the internet, based on his 1898 story “From the ‘London Times’ of 1904.” Twain’s narrator describes a device that seems to serve many of the same functions as the web:

As soon as the Paris contract released the telelectroscope, it was delivered to public use, and was soon connected with the telephonic systems of the whole world. The improved “limitless-distance” telephone was presently introduced, and the daily doings of the globe made visible to everybody, and audibly discussible, too, by witnesses separated by any number of leagues.

Like the internet, rooted in ARPANET, the telelectroscope is first explored for military applications before reaching civilian use. And like the internet, it proves to be a reliable way to kill time and monopolize its user’s attention, distracting him from social visitors:

He seldom spoke, and I never interrupted him when he was absorbed in this amusement. I sat in his parlor and read, and smoked, and the nights were very quiet and reposefully sociable, and I found them pleasant. Now and then I would her him say “Give me Yedo”; next, “Give me Hong Kong”; next, “Give me Melbourne.” And I smoked on, and read in comfort, while he wandered about the remote underworld, where the sun was shining in the sky, and the people were at their daily work. Sometimes the talk that came from those far regions through the microphone attachment interested me, and I listened.

The original TLS quest, for a first literary reference to the telephone, feels nearly as mustily poignant as an old-fashioned rotary phone—strangely fascinating, and yet entirely obsolete. In 2015, my colleague Adrienne LaFrance tried to figure out what the first TV show to refer to the internet was. Yet in addition to making it much easier to answer trivia questions of this variety, the internet also threatens to render them irrelevant. In Twain’s time, it would take days, weeks, or months to learn of fresh technologies like the telephone, understand them, incorporate them into writing, and have them published in print. The internet means that when a new technology arrives, it can be almost immediately understood and even more quickly incorporated into writing that can be published promptly online. A present-day Alonzo Fitz Clarence could while away a full cold Maine winter day reading that, without ever having to ring up his Aunt Susan in San Francisco./atlantic

del.icio.us

del.icio.us Digg

Digg

Post your comment