To stay or go into exile – Milosz and Szymborska

Many modern writers have become a species of nomad, living in exile because in their homelands freedom of speech is limited. One of the most important tasks of PEN International is to support imprisoned writers and journalists around the world, and there is more than enough to tackle there.

Written by Niels Hav *

Last year Patrick Modiano received the Nobel Prize for Literature and, as often before, it was a complete surprise when the secretary of the Swedish Academy opened the door and released the name to the press. Every year this event is a celebration, and the joyous news spreads round the world with the speed of light.

I was in Warsaw the year Tomas Tranströmer was awarded the Nobel Prize. Sitting in the mild October sunshine in front of the Literature-House with a group of poets from many contries. It was a few minutes past one, and Transrömer’s name passed cheerfully from table to table. Wizlawa Szymborska, Nobel prizewinner from Poland, was asked by a journalist, “What did you think when you heard that Transrömer won the Nobel Prize?” “I was so pleased,” she answered, “that I hopped on one foot.”

An unforgettable reply. At the time Szymborska was 88 years old, and the memory of her happy hop is a blessed thought.

Many modern writers have become a species of nomad, living in exile because in their homelands freedom of speech is limited. One of the most important tasks of PEN International is to support imprisoned writers and journalists around the world, and there is more than enough to tackle there.

The written word is regarded in some regimes as a threat, and censorship of both the internet and the printed media is well-known. To avoid criticism, some provide writers with free food and lodging in prison. Very generous, and totally idiotic – what a healthy society requires is free debate and free exchange of views. We do not live by bread alone. It is the duty of the state to support literature in every way; while it is the duty of the writer to write good books and, if necessary, to maintain a critical stance in relation to those in power.

Such is the distribution of roles in a healthy society. When Les Fleurs du mal was published in 1857, Charles Baudelaire was dragged into court and accused of blasphemy. Who was emperor or president at the time? No one remembers or cares today, the political figures have slipped back into the region of shadows, while Baudelaire’s book remains, an unchangeable masterpiece.

In Poland’s history, we find examples of the choice writers must face when freedom of expression is not respected – to stay, or to go into exile.

Wislawa Szymborska was born in 1923, she witnessed the Nazi depridation, followed by the Soviet époque of despotism. She stayed in Poland, living most of her life in Kraków, studied, taught and wrote poetry. She distanced herslf from the powerful and concentrated on her writing. Her collected works number some 350 poems. Asked why she had not published more, she answered, “I have a trash can at home.”

This ironic humour is also found in Szymborska’s poetry. Simple, everyday events are transformed by the power of metaphor into great poetry. Her work is full of an ordinary life’s inventory of objects and situations, as in the poem “Cat in an Empty Apartment”: the cat is alone at home with the furniture, lamps, carpets and bookshelf, while the owner is away – perhaps at work, perhaps dead.

In the famous poem “Nothing Twice”, Szymborska writes: “Nothing can ever happen twice./ In consequence, the sorry fact is / that we arrive here improvised / and leave without the chance to practice.” As for Szymborska, she died for the first and only time in 2012.

One of the nomads, one who chose exile is Czeslaw Milosz. Already in the 50s he left Poland and settled first in France, then in the USA where for many years he was a Professor of Slavic Languages and Literature at Berkeley, the University of California. In 1980 he received the Nobel Prize. After the upheavals in Poland and the fall of the Berlin Wall, he returned to his native land. It is 10 years now since his death. He was buried in Kraków as, later, was Szymborska.

But Czeslaw Milosz’s oeuvre is still of prime importance for lots of people world wide. His experiences in youth, trapped in between Nazism and Stalinism, may be compared to the situation faced by many writers today, with the world gain in the midst of great disruption and change. How do intellectuals adjust to a totalitarian state? Milosz has thoroughly explored this theme with an insider’s sensibility to its impossible paradoxes.

His work is pervaded by a strong ethos which, coupled with a robust irony, gives his poetry its lasting quality. In the poem “Arts poetica?” he writes: “Poems should be written rarely and reluctantly, / under unbearable duress and only with the hope / that good spirits, not evil ones, choose us for their instrument.”

In Warsaw, I enter a book store. Milosz and Szymborska are well represented on the shelves – autoboiographical works, essays, poems. I buy a cup of coffee, and spend an hour or so nosing among the books and leafing through the Polish journals. Finally I buy Proud to Be a Mammal by Czeslaw Milosz – it has to be the one.

I take the bus across the Wisla River to Praga, the only quarter in Warsaw that was not destroyed during the Second World War. The tumbled old houses in Praga have seen Poland rise again in the 30s, watched as Stalin’s and Hitler’s grandiose madness fell to ruin. German and Russian tanks, filled with nervous, cigarette-smoking young soldiers, rolled over these paving stones. Here Milosz could have walked in the 40s, newly composed poems in his shoulder bag, on his way to a reading or to meet a friend.

He relinquished his homeland, went into exile, turned his back on the proclamations of authority issuing from the corridors of power. This is why his poetry continues to be read, and he is remembered around the world. Most intensely by those who have felt, on their own foot, the pinch of the shoe.

( Translated by Heather Spears)

* * *

Ars Poetica?

By Czeslaw Milosz

I have always aspired to a more spacious form

that would be free from the claims of poetry or prose

and would let us understand each other without exposing

the author or reader to sublime agonies.

In the very essence of poetry there is something indecent:

a thing is brought forth which we didn’t know we had in us,

so we blink our eyes, as if a tiger had sprung out

and stood in the light, lashing his tail.

That’s why poetry is rightly said to be dictated by a daimonion,

though it’s an exaggeration to maintain that he must be an angel.

It’s hard to guess where that pride of poets comes from,

when so often they’re put to shame by the disclosure of their frailty.

What reasonable man would like to be a city of demons,

who behave as if they were at home, speak in many tongues,

and who, not satisfied with stealing his lips or hand,

work at changing his destiny for their convenience?

It’s true that what is morbid is highly valued today,

and so you may think that I am only joking

or that I’ve devised just one more means

of praising Art with the help of irony.

There was a time when only wise books were read,

helping us to bear our pain and misery.

This, after all, is not quite the same

as leafing through a thousand works fresh from psychiatric clinics.

And yet the world is different from what it seems to be

and we are other than how we see ourselves in our ravings.

People therefore preserve silent integrity,

thus earning the respect of their relatives and neighbors.

The purpose of poetry is to remind us

how difficult it is to remain just one person,

for our house is open, there are no keys in the doors,

and invisible guests come in and out at will.

What I’m saying here is not, I agree, poetry,

as poems should be written rarely and reluctantly,

under unbearable duress and only with the hope

that good spirits, not evil ones, choose us for their instrument.

[Czeslaw Milosz, “Ars Poetica?” from The Collected Poems: 1931-1987. Translated By Czeslaw Milosz and Lillian Vallee.]

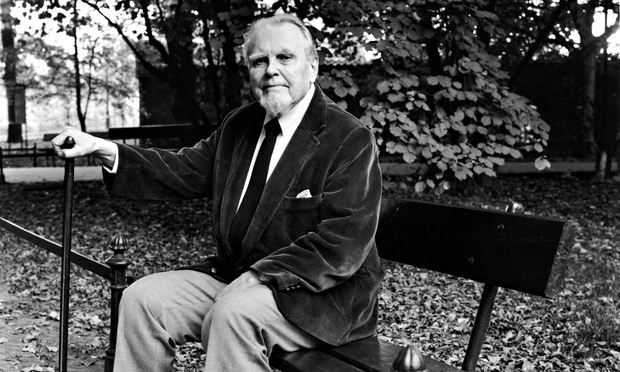

Czeslaw Milosz

* * *

Cat in an Empty Apartment

By Wisława Szymborska

Die — you can’t do that to a cat.

Since what can a cat do

in an empty apartment?

Climb the walls?

Rub up against the furniture?

Nothing seems different here

but nothing is the same.

Nothing’s been moved

but there’s more space.

And at nighttime no lamps are lit.

Footsteps on the staircase,

but they’re new ones.

The hand that puts fish on the saucer

has changed, too.

Something doesn’t start

at its usual time.

Something doesn’t happen

as it should.

Someone was always, always here,

then suddenly disappeared

and stubbornly stays disappeared.

Every closet’s been examined.

Every shelf has been explored.

Excavations under the carpet turned up nothing.

A commandment was even broken:

papers scattered everywhere.

What remains to be done.

Just sleep and wait.

Just wait till he turns up,

just let him show his face.

Will he ever get a lesson

on what not to do to a cat.

Sidle toward him

as if unwilling

and ever so slow

on visibly offended paws,

and no leaps or squeals at least to start

[Wisława Szymborska, translated from the Polish by Stanisław Barańczak and Clare Cavanagh.]

Wisława Szymborska

About the Author *

Niels Hav is a full time poet and short story writer living in Copenhagen. He has already established himself as a contemporary Nordic voice with poetry and fiction published in numerous journals and anthologies in e.g. English, Arabic, Spanish, Italian, Turkish, Dutch, Chinese. But it is in Canada in particular that he has made his mark outside Denmark. An English collection of his poetry, God’s Blue Morris, was published by Crane Editions in 1993, with a second collection, entitled We Are Here, put out by Book Thug of Toronto in 2006. Both of them translated con amore by Patrick Friesen and Per K. Brask. Most recently a selection of Niels Hav’s poetry, U Odbranu Pesnika, has appeared in Serbian translation, published by RAD, Belgrade 2008. Raised on a farm in western Denmark, Niels Hav today resides in the most colourful and multiethnic part of the Danish capital. He has travelled widely in Europe, Asia, North and South America. In his native Danish he is the author of three books of short fiction and five collections of poetry, most recently Grundstof, Gyldendal 2004. Niels Hav has received a number of prestigious awards from The Danish Arts Council.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us Digg

Digg

Post your comment