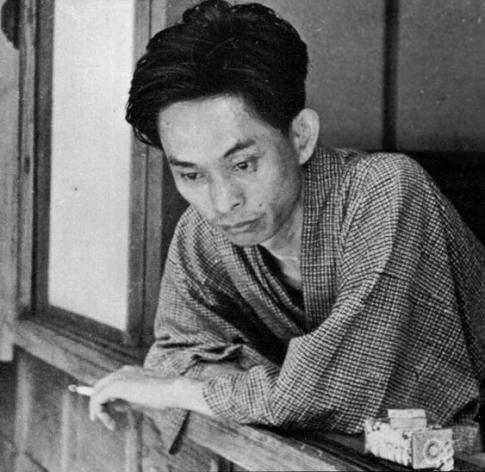

Yasunari Kawabata (1899-1972)

Yasunari Kawabata became the first Japanese novelist to win the Nobel Prize for Literature. His works combined the beauty of old Japan with modernist trends, and his prose blended realism with surrealistic visions.

In 1968, Yasunari Kawabata became the first Japanese novelist to win the Nobel Prize for Literature. His works combined the beauty of old Japan with modernist trends, and his prose blended realism with surrealistic visions. Kawabata's books have been described as "melancholy lyricism" and often explore the place of sex within culture, and within individual lives. Over the course of his life, Kawabata wrote many novels and more than a hundred two or three page stories. He called these his "tanagokoro no shosetsu" (palm-of-the-hand stories), and said that they expressed the essence of his art. An example of one of these stories is Ki-no Ue (Up in the Tree, 1962). Here, the main characters, a girl and a boy named Michiko and Keisuke, both fourth graders, share a secret. Keisuke tells Michiko that his parents quarrel, and his father has another woman. He once climbed a tree in the garden so that his mother couldn't take him and go back to her parents' house. Since then he has been up in that tree a lot.

"The "secret" of their being up in the tree had continued for almost two years now. Where the thick trunk branched out near the top, the two could sit comfortably. Michiko, straddling one branch, leaned back against another. There were days when little birds came and days when the wind sang through the pine needles. Although they weren't that high off the ground, these two little lovers felt as if they were in a completely different world, far away from the earth." (from 'Up in the Tree')

Yasunari Kawabata was born into a prosperous family in Osaka, Japan. His father, Eikichi Kawabata, was a prominent physician, who died of tuberculosis when Yasunari was just two. He was orphaned by the death of his mother at age three, his grandmother died when he was seven, and his only sister when he was nine. The family deaths deprived Kawabata of a normal childhood, and he often said that he learned loneliness and rootlessness early. Later in life the author described himself as a child "without home or family." Some critics feel that these early traumas form the background for the sense of loss and regret which permeate his writing.

After losing his grandfather in 1915, Kawabata moved to a middle-school dormitory. He began studying literature at Tokyo Imperial University in 1920, graduating in 1924. Kawabata and a group of young writers founded the journal Bungei Jidai "The Artistic Age." With this journal, they advocated for a literary movement called Shinkankaku (Neo-Sensualism), which opposed the then dominant "realistic" school of writing. Kawabata was interested in European avant-garde literature, and also wrote the film script for Kinugasa Teinosuke's expressionist movie, Kuritta Ippeji (A Page of Madness, 1926).

Kawabata gained his first critical success with the novella Izu-no Odoriko (The Izu Dancer, 1925). The autobiographical work recounted his youthful infatuation with a fourteen-year-old dancer, whose legs streched "up like a paulownia sapling". The story ends with their separation. Young women also appear prominently in other Kawabata's works, such as Nemureru Bijo (Sleeping Beauty, 1961) and the short novel Tanpopo (Dandelion, published posthumously).

The fragmented novel Asakusa Kurenaidan (The Scarlet Gang of Asakusa, 1929-1930), was set in the Asakusa district of Tokyo, famous for its geisha houses, dancers, bars, prostitutes, and theaters. The novel was serialized in the Asashi Shimbun newspaper, bringing modernist, experimental fiction to a wider audience within Japan. Kawabata was married in 1931, and afterward settled in the ancient samurai capital of Kamakura, southwest of Tokyo, spending the winters in Zushi. During World War II, Kawabata traveled in Manchuria, and studied Genji Monogatari (The Tale of Genji), an eleventh-century Japanese novel.

Soon after the war, Kawabata published his most famous novel, Yukiguni (The Snow Country, 1948), the story of a middle-aged aesthete, Shimamura, and an aging geisha, Komako. Their sporadic affair is conducted intermittently in an isolated location; a hot spring resort west of the central mountains, where winters are dark, long and silent. Shimamura thinks to himself , "After all, these fingers keep a vivid memory of the woman I am going to see," when he travels to the snow country by train. It takes him to another place, away from the ballet book he is writing, away from his mundane life. But this far-off destination gives him only a temporary home, a reflection of something else when night transforms the coach's window into a mirror. Geisha is a performance artist and Shimamura doesn't know, whether her affection is really genuine. Komako bites his finger; she is not a reflection, created according to Shimamura's aesthetic vision, she is a physical being. Kawabata later mentioned that he modeled her after a real character. Yukiguni has been filmed several times, Shiro Toyoda version from 1957, starring Kishi Keiko as Komako and Ryo Ikebe as Shimamura, is considered the most successful.

"In the depths of the mirror the evening landscape moved by, the mirror and the reflected figures like motion pictures superimposed one on the other. The figures and the background were unrelated, and yet the figures, transparent and intangible, and the background, dim in the gathering darkness, melted into a sort of symbolic world not of this world. Particularly when a light out in the mountains shone in the center of the girl's face, Shimamura felt his chest rise at the inexpressible beauty of it." (From The Snow Country)

Considered by some critics to be Kawabata's best work, Yama-no Oto (The Sound of the Mountains, 1954), depicts a family crisis in a series of linked episodes. The protagonist, Shingo, represents the traditional Japanese values of in human relationships and nature. He is concerned about the marital crises of his two children. Scenes from this hero's daily life are interwoven with poetic descriptions of nature, dreams, and recollections. This work earned Kawabata the literary prize of the Japanese Academy. Kawabata combined refined Japanese aesthetics with psychological narrative and eroticism. In his early fiction Kawabata experimented with surrealistic techniques, but in his later writings, his naturalistic style became more impressionistic.

Senbazuru (A Thousand Cranes, 1952), used the traditional Japanese tea ceremony as a background to a story based on the classical work Genji Monogatari (The Tale of Genji). In Utsukushisa-to Kanashimi-to (Beauty and Sadness, 1965), Kawabata told of the reunion of an elderly man and a woman artist, and the revenge of the artist's young protégée. In this tale, as in other works of his later life, Kawabata's approach is open-ended; more is implied, left to the imagination of the readers, than is made explicit.

One of his lesser known novels in the west, Meijin (The Master of Go, 1972), was a fictionalized account of an actual 1938 Go match between an old champion and a young challenger. Go is Japan's ancient game of strategy and a Go match is concerned with the game itself, and with respect for tradition and ancient rites. Kawabata's retelling of the match (which he covered as a reporter for the Japanese newspaper Asahi Shimbun), reflects the tension between old traditions and new pragmatism. In the story, the players are isolated during parts of the match, and and finally, when the players emerge from isolation, the tradition of Go itself has lost. Kawabata considered this his finest piece of writing, although it is stark and spare compared to his other works. Many critics consider this work to be Kawabata's commentary on the Japanese culture and World War II.

As he grew older, Kawabata became famous as a writer around the world. In the 1960s, before receiving the Nobel Prize, Kawabata made a tour in the United States, lecturing in universities. In the late 1960s Kawabata campaigned for conservative political candidates in Japan and, with Yukio Mishima and other writers, signed an address condemning the Cultural Revolution in China. He was also president of the Japanese PEN club and active in helping aspiring writers. Kawabata condemned suicide in his Nobel acceptance speech, perhaps remembering several of his fellow writers who had died by their own hands. However, Kawabata had long suffered from poor health, and on April 16, 1972, two years after Mishima's suicide, Kawabata committed suicide at his home in Zushi by gassing himself. He left no note.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us Digg

Digg

Post your comment