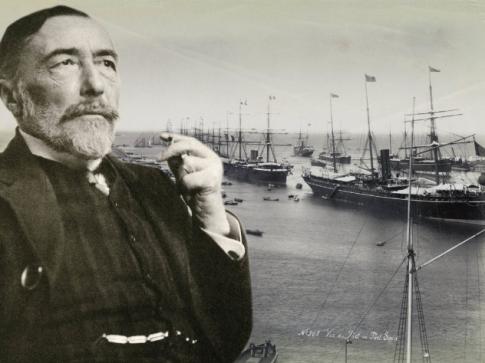

Joseph Conrad (1857 - 1924)

Joseph Conrad - Polish noble, English writer, sailor.

Joseph Conrad (Józef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski) - Polish noble, English writer, sailor. Born December 3, 1857 in Berdichev (now Ukraine), died August 3, 1924 in Oswalds, near Canterbury, Great Britain

Joseph Conrad was born the son of Apollo Korzeniowski and Ewa née Bobrowska, in Berdyczów (now Berdychiv, Ukraine) on December 3, 1857. Both parents were Polish and members of the local szlachta, the land-owning gentry-nobility (there was no legal distinction between these two classes in Poland); both were devout Roman Catholics. Until the partition of Poland between Russia, Austria-Hungary and Prussia at the end of the 18th century, Central and Western Ukraine constituted a part of the multinational Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, most of the gentry were ethnic Poles, most of the town-dwellers were Jewish, and most of the peasantry, Ukrainians ("Ruthenians"). Conrad's ancestors had settled there in the late 17th century.

Conrad's paternal grandfather, Teodor Korzeniowski, captain of the Polish army during the 1830 Insurrection against Russian rule, lost his estate in the political turbulence caused by the partitions. He had one daughter, Emilia, sent to exile in Russia in 1864, and three sons: Robert, killed in the 1863 Insurrection, Hilary, who died in 1878 while in compulsory exile in Siberia after the same insurrection, and Apollo, born in 1820. Apollo had a gift for languages and writing. He studied at St Petersburg University and later supported himself by managing landed estates, writing satirical comedies (his satire, tempered by censorship, was patriotic and democratic in spirit and directed against materialism and the political opportunism of Polish landowners), and translating from English (Dickens and Shakespeare), French (Victor Hugo and Alfred de Vigny) and German (Heine). He also wrote and circulated manuscripts of patriotic and religious poems in which he expressed his sympathy for the oppressed Ukrainian peasantry and exhorted Poles to show unswerving fidelity to the cause of national independence.

The author of The Heart of Darkness, Nostromo, and Lord Jim was born and grew up in partitioned Poland. Yet his literary work is ostensibly devoid of almost any traces of his background. So where should one look for Conrad’s Polishness?

After the birth of Józef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski, his father, Apollo, wrote the following "Baptismal Poem" for his son:

Baby son, tell yourself

You are without land, without love,

Without country, without people,

While Poland - your Mother is in her grave.

In April 1861, Apollo Korzeniowski moved to Warsaw, ostensibly to start a cultural periodical, but in fact to organise underground resistance to the Russian authorities. In October 1861, he formed a clandestine "Committee of the Movement" which was the kernel of the underground National Government of 1863. A few days later, he was imprisoned in the Warsaw Citadel.

Ewa Korzeniowska and her son followed Apollo to Warsaw in October 1861, and witnessed his arrest. Ewa was also charged and questioned, but not placed in custody. Little Conrad would accompany his grandmother when she carried supplies to his imprisoned and ailing father. He wrote later that "In the courtyard of this [Warsaw] Citadel - characteristically for our nation - my childhood memories begin". The investigation, by military tribunal, of the Korzeniowski family lasted until April 1862, but the verdict, issued in fact by the viceroy of Poland, a Russian general, preceded by two weeks the official decision of the court. Although only circumstantial evidence was produced against both Ewa and Apollo, they were sentenced to exile in Northern Russia "under strict police supervision". The viceroy added in his own hand: "Mind that they do not stop on the way". They were dispatched to Vologda, known for its harsh climate.

In January 1863, for health reasons, they were allowed to move to Chernihiv, in north-eastern Ukraine. There, Ewa Korzeniowska died of tuberculosis in April, 1865. Apollo was also gravely ill, and was released from exile in January, 1868. He left with his son to Lwów (Lviv), an important centre of Polish culture in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and later they moved to Kraków, the ancient capital of Poland. Konrad was first educated by his father but when Apollo died in May, 1869, Konrad's maternal uncle, Tadeusz Bobrowski, became his guardian and benefactor. A sickly boy, Konrad did not attend school regularly, but was instead taught at home by private tutors. He passed his formal exams, first in Kraków, then later in Lviv. In the autumn of 1874, he was sent - partly for health reasons - to Southern France, with a view to embarking on a maritime career.

Initially, Korzeniowski did not want to leave Poland permanently; in 1883, he assured one of his father's friends that he would remember the pledge that "wherever he may sail he is sailing towards Poland". Yet, as a Russian subject and a son of convicted parents, he was liable for long military service, and his attempts to be exonerated from the allegations of the Russian State succeeded only in 1889. By that time, he had switched from the French to the British merchant fleet marine (in 1878) and had passed his examinations for master mariner (1886). That same year, he became a British subject. Though he kept up correspondence with his uncle, and visited his home country in 1889 and 1893, Korzeniowski's letters to him were destroyed during the Bolshevik Revolution. However, Bobrowski's letters of reply survived, and they constitute the most important biographical source of Korzeniowski's early years. Though he did not ever officially change his name, Korzeniowski assumed the pen-name of Joseph Conrad when he published his first novel, Almayer's Folly(1895), dedicated to the memory of Tadeusz Bobrowski who had died a year earlier, thus severing Conrad's last personal link with Poland.

For the first 20 years of his writing career, Conrad struggled with debts: his royalties fell far below his modest expenses. In summer 1914, he was able to take his first long vacation, taking his wife and two sons to Poland. The outbreak of the First World War caught them in Kraków; they spent two months in the city and then went south, to the Tatra Mountains. While in Kraków and Zakopane, Conrad met several Polish writers, artists and intellectuals. This was to be his last visit to his native country.

The reminiscences of his relatives and friends testify to Conrad's continued emotional involvement in the affairs, traditions, and culture of Poland. For example, at his country home in Kent, he would organise private recitals of Chopin's music.

At his funeral (he died near Canterbury on August 3, 1924), the only official present was a representative of the Prime Minister of Poland.

From the letters of Apollo Korzeniowski to his friends, we know that the young Conrad was an avid reader. He was certainly well acquainted with classical Polish literature, beginning with the work of the great sixteenth-century poet, Jan Kochanowski (whom he mentions in his letters). It is very likely that the poetry, drama and fiction of the Polish romantic writers (of whom his father was an epigone) formed the main body of his reading in his native language. "Polonism I have taken into my works from Mickiewicz and Słowacki", he declared in 1914, mentioning by name the two greatest writers, and moral and political authorities, of Polish romanticism.

Ideas of moral and national responsibility pervaded this literature. Fidelity and betrayal, honour and shame, duty and escape were frequent themes. The moral problems of an individual were typically posed in terms of communal obligations, and ethical principles, formed under the decisive influence of chivalry, were also grounded in the idea that an individual, however exceptional, is always a member of a community. A poet was a typical example of an exceptional individual, burdened with special duties towards his nation. The passage "from alienation to commitment", recognised as a frequent theme in Conrad's fiction, has been a staple subject of Polish romantic literature (as in Mickiewicz's Pan Tadeusz and Forefather's Eve). One of the more popular literary forms was the tale (gawęda), a story told by a personal narrator who is often one of the protagonists, and it is easy to find a continuation of this form in Conrad's narratives.

Apart from the general presence of important elements of the Polish cultural tradition, critics have identified in Conrad's writings many thematic, artistic, and verbal motifs taken from particular works of Polish literature. The Polish language itself also left its mark on Conrad's prose. Not only in the form of Polonisms (words and idioms used in their Polish rather than English sense), but also in occasional errors in the use of tenses, and an infrequent looseness of syntax. The rhetorical, rolling rhythm of his phrases can also be traced back to the influence of his native speech.

How Joseph Conrad Formed an Identity as an English Novelist

Joseph Conrad's idea of England and Englishness was formed early in his career. Culture.pl presents an academic paper by Allan H. Simmons addressing Conrad's engagement with his adoptive country as part of shaping his identity and writings.

In his essay "Autocracy and War" (1905), Conrad's most important political statement, Poland is mentioned as a victim of German and Russian imperialism, linking those two countries in their "common guilt".

A Personal Record (1912) contains long and moving fragments recounting his early Polish experiences and members of his closest family. Prince Roman (1910), included in the posthumous volume Tales of Hearsay is a tale about Prince Roman S[anguszko] who "from conviction" joined the forces of the Polish uprising against Russian power in November 1830. Once captured, he was sentenced to hard labour in Siberian mines. Conrad describes Poland as:

That country which demands to be loved as no other country has even been loved, with the mournful affection one bears for the unforgotten dead and with the inextinguishable fire of a hopeless passion which only a living, breathing, warm ideal can kindle in our breast for our pride, for our weariness, for our exultation, for our undoing.

In 1914, inspired by fresh contacts with his compatriots, Conrad wrote a Memorandum outlining his plans of action in the UK in support of Polish interests. His essay "Poland Revisited" (included later in his Notes on Life and Letters, 1921) describes Conrad's journey to Poland and reflects his dismay at the British attitude of considering the future of Poland as Russia's internal affair. Two years later in a special "Note on the Polish Question" (published also in Notes...), addressed to the British Foreign Office, he proposed a reconstruction of Poland under the protectorate of Great Britain and France ("Quite impossible. Russia will never share her interests in Poland with Western Powers" was the negative reply).

In 1918, Conrad greeted the re-emergence of an independent Poland (after 123 years of the partitions) with joy, relief, and an embarrassment caused by his own lack of faith that it would ever happen. He wrote an emotional appeal in support of the new country and in remembrance of its sufferings, "The Crime of Partition" (1919, included in Notes...). In 1920, while the Polish army was fighting for the survival of the country against a Soviet invasion, he sent a telegram in support of the Polish Government Loan:

For Poles the sense of duty and the imperishable feeling of nationality preserved in the hearts and defended by the hands of their immediate ancestors in open struggles against the might of three Powers and in indomitable defiance of crushing oppression for more than a hundred years is sufficient inducement to come forward to assist in reconstructing the independence, dignity and usefulness of the reborn Republic.

Some Polish intellectuals accused Conrad of betraying his native country because he chose to write in English. This was most clearly articulated in an article, published in 1899, by a well-known and respected Polish woman-novelist, Eliza Orzeszkowa. Conrad took this accusation to heart, and a couple of years later, in 1901, he declared to a Kraków librarian, Józef Korzeniowski (not related):

I have in no way disavowed either my nationality or the name we share [...] It is widely known that I am a Pole and that Józef Konrad are my two Christian names, the latter being used by me as a surname so that foreign mouths should not distort my real surname [...] It does not seem to me that I have been unfaithful to my country by having proved to the English that a gentleman from the Ukraine can be as good a sailor as they, and has something to tell them in their own language. I consider such recognition as I have won from this particular point of view, and offer in silent homage where it is due.

Writing the Self: Europe as Autobiography for Joseph Conrad

Joseph Conrad's A Personal Record serves as a document of identity construction at a time when the modern-day idea of 'Europe' and 'The West' were being shaped. Culture.pl presents an academic paper by Asako Nakai which explores the parallels between writing about a self at a time when the idea of writing as a European was undergoing a transformation.

He was by that time becoming known in Poland: the first ever translation of his work (An Outcast of the Islands) was published in a Warsaw periodical in 1897, and other translations followed.

In 1914, he gave his first ever interview to a Polish journalist, Marian Dabrowski (husband of Maria Dabrowska later one of the most distinguished Polish twentieth-century novelists and the author of a volume of essays on Conrad). During the interview, Conrad confessed that his father had read to him Mickiewicz's long poem Pan Tadeusz, "not just once or twice", also making him read it aloud. He "used to prefer Konrad Wallenrod and Grażyna ", Mickiewicz's shorter poetic tales. "Later I liked Słowacki better. You know why Słowacki? Il est l'ame de toute la Pologne, lui." [He is the soul of all Poland, he is.]

Conrad's contacts with Polish writers and readers became closer after 1920. He corresponded with several authors and translators, and, in 1921, he himself translated from Polish a comedy by Bruno Winawer (The Book of Job, published posthumously). The most eminent Polish writer of the time, Stefan Żeromski, the moral authority of Polish liberals and socialists, wrote an enthusiastic introduction to a collected edition of Conrad's works, calling him a "writer-compatriot". Conrad responded with a letter:

I confess that I cannot find words to describe my profound emotion when I read this appreciation from my country, voiced by you, dear Sir - the greatest master of its literature.

In the 1920s and '30s, Conrad became a very influential writer in Poland, much read and discussed both by intellectuals and by the wider reading public, with whom his sea fiction was especially popular. He reached the peak of his popularity in the darkest hours of modern Polish history, during World War II, when the country was again invaded by its German and Soviet neighbours. Conrad, and particularly the Conrad of Lord Jim, became one of the leading moral authorities for the young members of the Polish underground army and civil resistance.

The first ever full edition of Conrad's works (27 volumes) was published in Poland in 1972-74, with one supplementary volume containing material confiscated by the Communist censors, and published by Polish émigrés in London.

The hospital in which Conrad was born in Berdychiv no longer exists. In the town, there is a small Joseph Conrad museum in the premises of a magnificent Carmelite Monastery (a priest from this monastery baptised Conrad). A commemorative plaque in the centre of Warsaw (Nowy Świat Street) was placed on the house next to the one in which the Korzeniowskis rented their flat in 1862. The cell in the Warsaw Citadel in which Conrad's father was imprisoned still exists. So does the house in which Conrad lived with his father in Kraków on Poselska Street, and the buildings where he stayed as a boarder in Lviv and Kraków (Floriańska Street)

Two volumes of Apollo Korzeniowski's manuscripts, most of them unpublished, are preserved in the Jagiellonian Library in Kraków. Several important letters and documents concerning Conrad himself are to be found in the PAN Library, also in Kraków. The National Library in Warsaw holds Tadeusz Bobrowski's letters to Conrad, and several of Conrad's letters in Polish. Outside Poland, the most important collection of Conrad's manuscripts connected with his Polish background are kept at the Beinecke Library, Yale University, and in the Polish Library in London.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us Digg

Digg

Post your comment